Hollywood’s version of science often asks us to believe that dinosaurs can be cloned from ancient DNA (they can’t), or that the next ice age could develop in just a few days (it couldn’t).

But Pixar’s film Inside Out is an animated fantasy that remains remarkably true to what scientists have learned about the mind, emotion and memory.

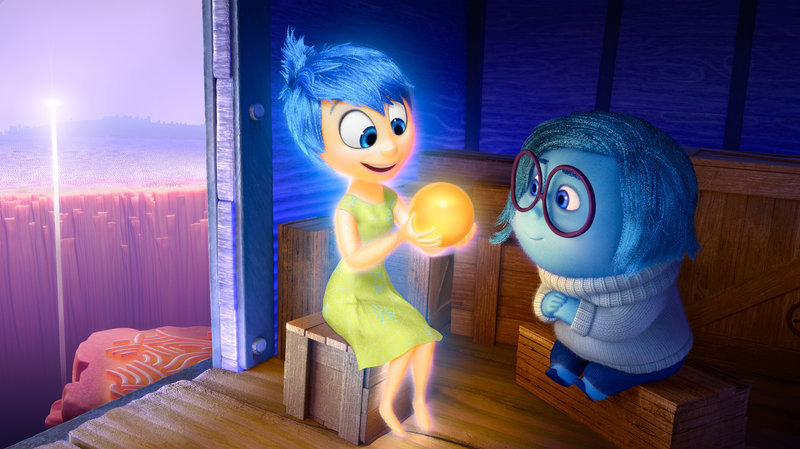

The film is about an 11-year-old girl named Riley who moves from her happy home in Minnesota to the West Coast, where she has no friends and pizza is made with broccoli. Much of the film is spent inside Riley’s mind, which features a control center manned by five personified emotions: Joy, Sadness, Fear, Anger and Disgust.

“I think they really nailed it,” says Dacher Keltner, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley who worked as a consultant to the filmmakers.

The movie does a really good job of portraying what it’s like to be 11, Keltner says. “It zeroes in on one of the most poignant times in an individual’s life, which is the transition to the preteen and early teen years, where kids — and, I think, in particular girls — start to really powerfully feel the loss of childhood,” he says.

As the filmmakers were working, they would fire off emails to Keltner and to Paul Ekman, a pioneer in the study of emotions. The process helped create a movie that’s true to the underlying science when it shows things like how emotions tend to color Riley’s perception of the world.

“When you are in a fearful state, everything is imbued with threat and uncertainty and peril,” Keltner says. And when Riley is sad, he says, even her happy memories take on a bluish hue.

The filmmakers get a lot of other scientific details right. Inside Riley’s head, you see memories get locked in during sleep, experiences transformed into abstractions, and guards protecting the subconscious.

There are a few departures from the scientific norm. Long-term memories are portrayed as immutable snow globes, though scientists know these memories actually tend to change over time. And Riley gets five basic emotions instead of the six often described in textbooks. (“Surprise,” apparently, didn’t make the cut.)

Also disgust is present in a pretty mild form — the reaction a child has to eating broccoli. The film plays down a more powerful version of disgust, “like if you suddenly eat a piece of food and it has a worm in it, or it’s rotting, Keltner says.

One of the film’s high points, though, is its depiction of sadness, Keltner says. In many books and movies for kids, he says, sadness is dismissed as a negative emotion with no important role.

In Inside Out, star-shaped Joy gets more screen time. But when the emotions are in danger of getting lost in the endless corridors of long-term memory, it is Sadness, downcast and shaped like a blue teardrop, who emerges as an unlikely heroine.

For kids, Keltner says, that makes “a nice statement about how important sadness is to our understanding of who we are.”